**NEW PUBLICATION**

The adverse effects of in-flight icing on small fixed-wing UAVs are a research topic with increasing interest. While the research primarily focuses on clean wing configurations, the impact of leading-edge ice accretion on the aerodynamic performance with deflected control surfaces has been neglected. However, ice accretion has a significant effect on the flow field downstream.

Modeling Iced Airfoils with Deflected Control Surfaces

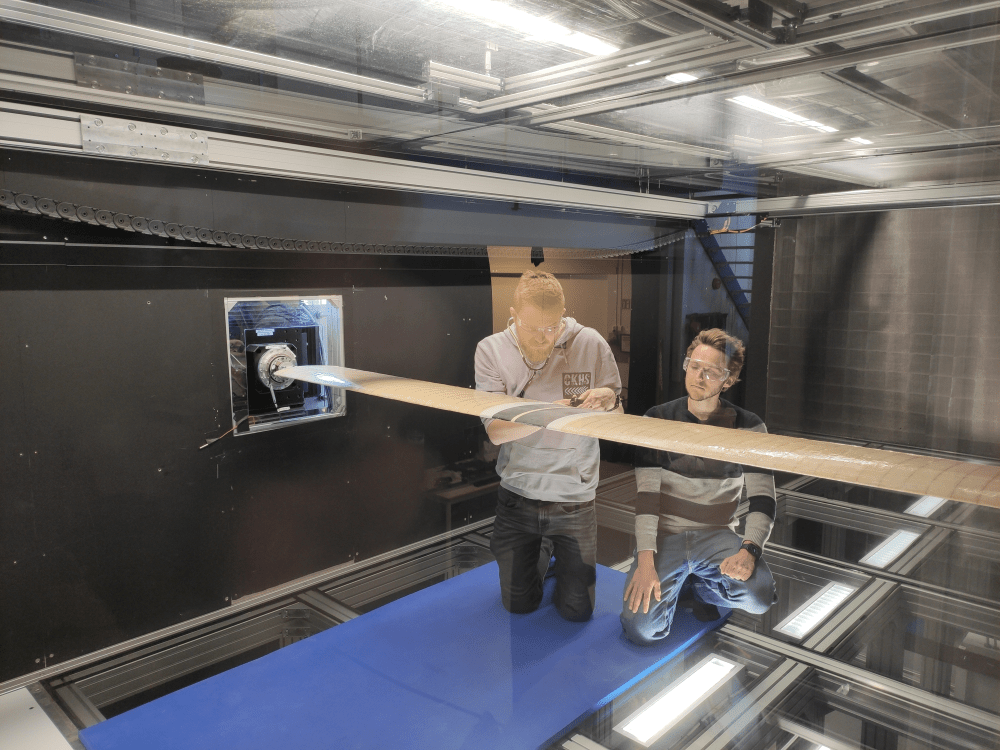

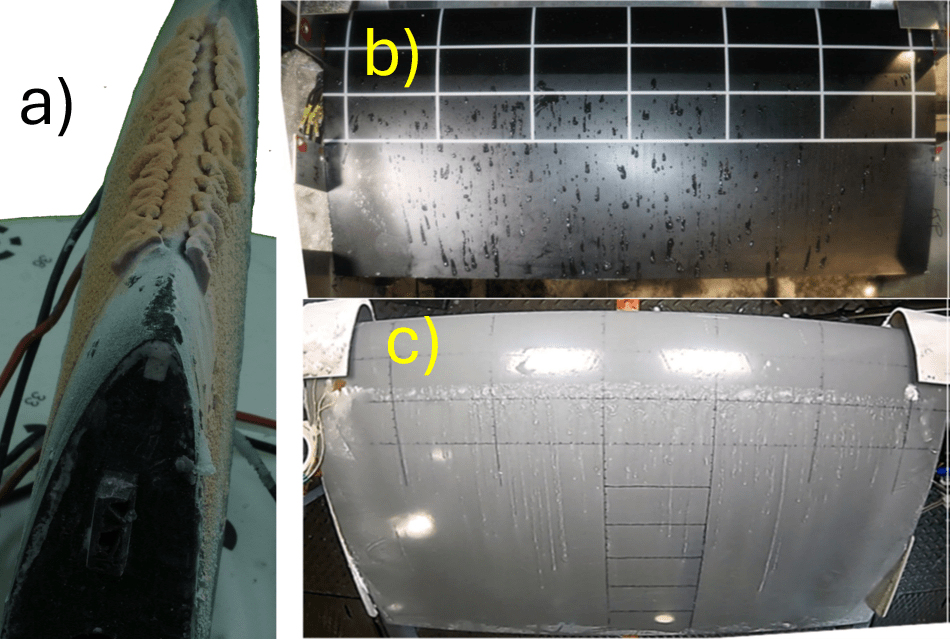

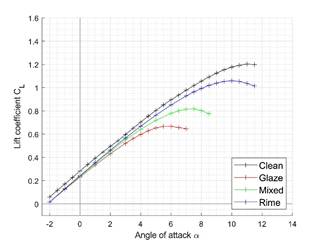

In previous icing wind tunnel campaigns, experimental ice shapes were accreted using an RG-15 airfoil with 30 cm chord length. The temperatures during the ice accretion process have an influence on the shape of the resulting ice. Typically, three different ice types are distinguished: rime, mixed, and glaze ice, with rime being the coldest. In this set-up, these ice types were achieved at –10, –4, and -2 °C, respectively, at an airspeed of 25 m/s and a liquid water content of 0.52 g/m^3. After an ice accretion time of 20 min, the ice shapes were digitized and the maximum combined cross-section (MCCS) calculated.

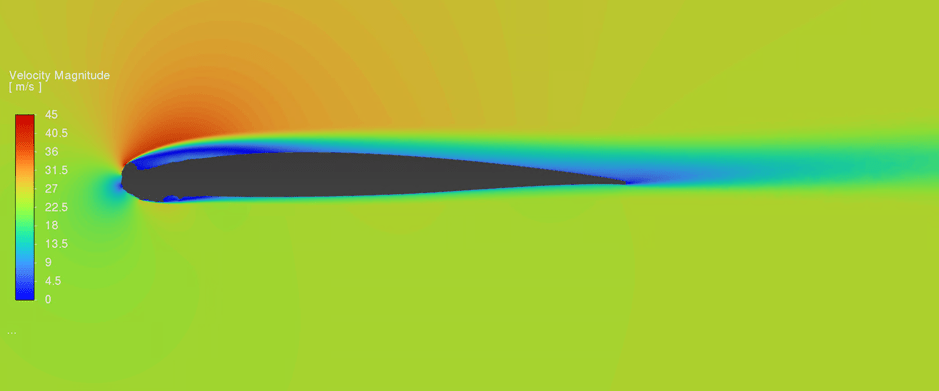

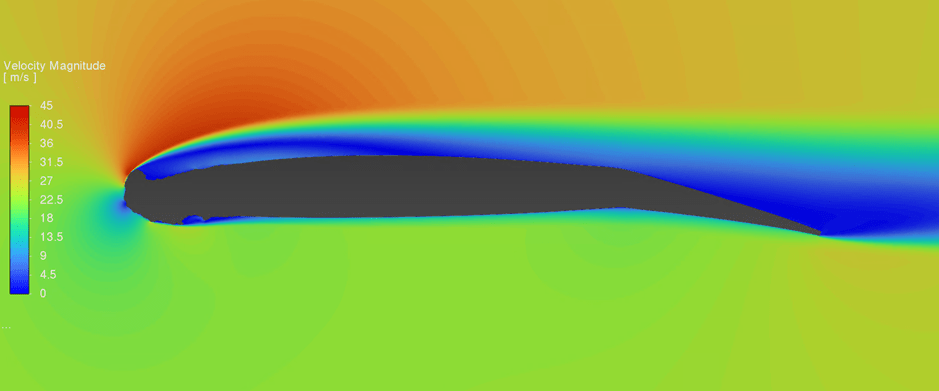

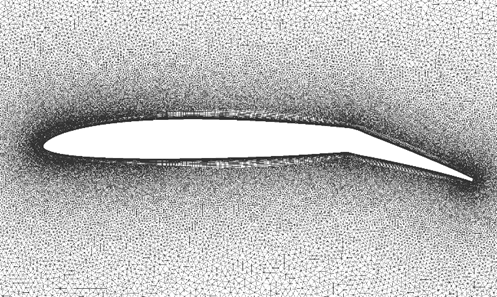

Since the actual investigation is done using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, the MCCSs of the ice shapes are attached to the leading edge of an RG-15 airfoil in a meshing software. The control surface, which in this context can be an aileron or flap, is represented by a deflection of the airfoil starting at 70% chord-wise position. The goal of this study is to see the change in aerodynamic performance of an airfoil at different control surface deflections with and without ice accretion. This study compares five deflection angles, -5 °, 0°, 5°, 10°, and 15° (downward deflection positive), for the three ice shapes and the un-iced wing. It is especially of interest to see how a deflection of the control surface changes the lift, drag, and generated moments, and how this is affected by icing.

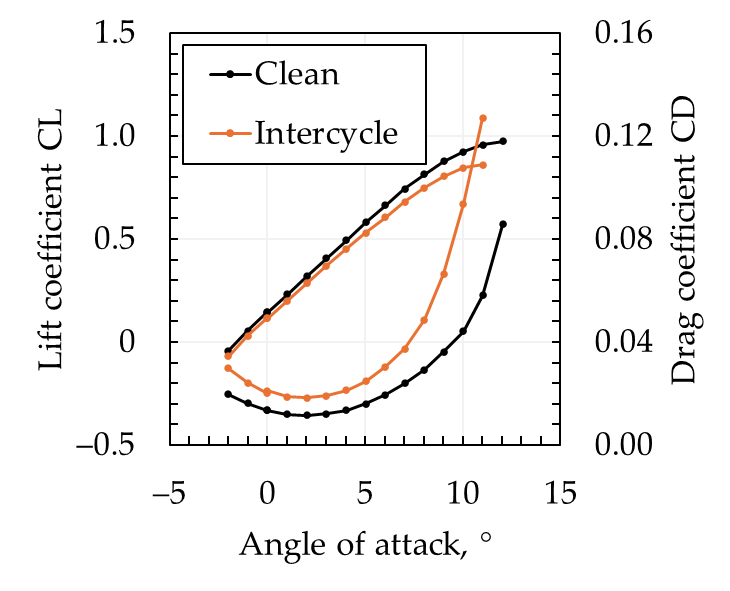

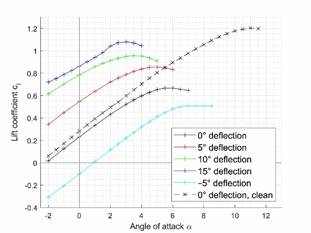

The Combined Effect of Ice and Deflected Control Surfaces on Lift

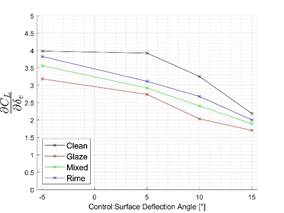

The (positive) deflection of a control surface on an un-iced airfoil increases lift coefficient and decreases the stall angle. Leading-edge ice accretion decreases both the lift coefficient and the stall angle. Combining both effects can result in hazardous flight situations. Looking at glaze ice as the most severe ice shape in terms of aerodynamic performance degradation, this effect becomes apparent. The undeflected case already shows a significant reduction in max. lift coefficient compared to the un-iced case. Deflecting the control surface shows the expected effect of increased lift; however, in a significantly reduced magnitude, not reaching the un-iced max. lift even at a 15° deflection angle. The results for the rime and mixed ice cases can be found in the corresponding publication.

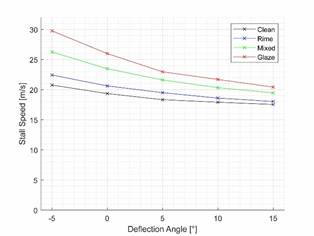

The reduction of the stall angle and thereby the max. lift coefficient has implications on the stall speed, i.e., the min. required velocity to be able to maintain horizontal flight at the stall angle. In all iced cases, this velocity is increased, most severely for glaze. The higher velocity of the UAV produces more drag, which the thrust of the propeller must match. However, the drag coefficient is also impacted by the deflection of the control surface.

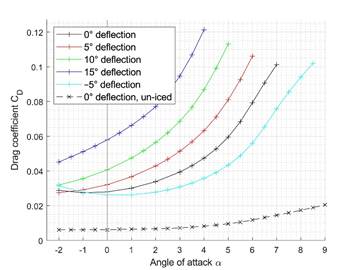

What about the Drag?

The drag coefficient paints an even worse picture than the lift coefficient. Again, comparing the results of the glaze ice cases, already the ice accretion increases the drag coefficient by 480% at an angle of attack of 4°. Deflecting the control surface, the drag coefficient increases by 450%, 440%, 330%, and 190% for −5°, 5°, 10°, and 15°, respectively, compared to the corresponding un-iced deflection angles. In combination with the higher flight velocity or higher angle of attack, the thrust that the propeller can provide (given it is protected against ice accretion) might reach its limit. Nevertheless, this depends on the individual UAV and the propeller.

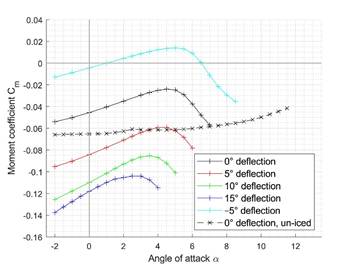

Longitudinal Stability and Control of Iced Airfoils

A third part of this investigation focuses on the impact on longitudinal stability and controllability of iced UAV wings. To evaluate the longitudinal stability of an airfoil against disturbances, the gradient of the curve is significant. A negative gradient indicates a statically stable behaviour, meaning the airfoil creates a moment to return to the initial flight attitude after a disturbance. While the un-iced pitching moment coefficient curve have mostly a negative gradient, all iced simulations feature a significantly greater positive gradient, revealing considerably more unstable behaviour. The curves of the pitching moment for the glaze ice cases can be found in the picture below.

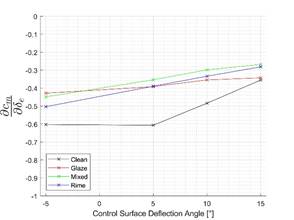

The longitudinal control derivative 𝐶𝑚𝛿e is defined as the change in moment when deflecting the control surface. This can be used in a simulator to study the flight behavior of an iced UAV. The figure below displays the control derivatives 𝐶𝑚𝛿e for the un-iced wing and with leading-edge ice accretion of three ice types for an angle of attack of 4°. Two aspects can be observed: First, the control surface effectiveness is reduced in comparison with the un-iced case. This means that, with the same deflection, less moment is generated, requiring greater deflection of the control surfaces, with all the downsides discussed earlier: reduced stall margins and increased drag. Secondly, while the change in moments generated when deflecting upward and downward is the same in the un-iced case, this no longer applies in the iced cases, leading potentially to unexpected behaviour when the control surfaces are used as ailerons and are deflected in opposite directions.

Summary

Leading-edge ice accretion has a severe impact on the aerodynamic performance of a small fixed-wing UAV. When downstream of the ice accretion a control surface is deflected, the adverse effects are amplified, potentially causing hazardous flight conditions that can lead to the loss of the aircraft. The deflection of the control surfaces further reduces stall margin, increases drag, and reduces the control surface effectiveness. This further stresses the need for mitigation strategies against in-flight icing, methods to reliably detect icing conditions, and methods to estimate the UAV’s aerodynamic state.

Text: Markus Lindner

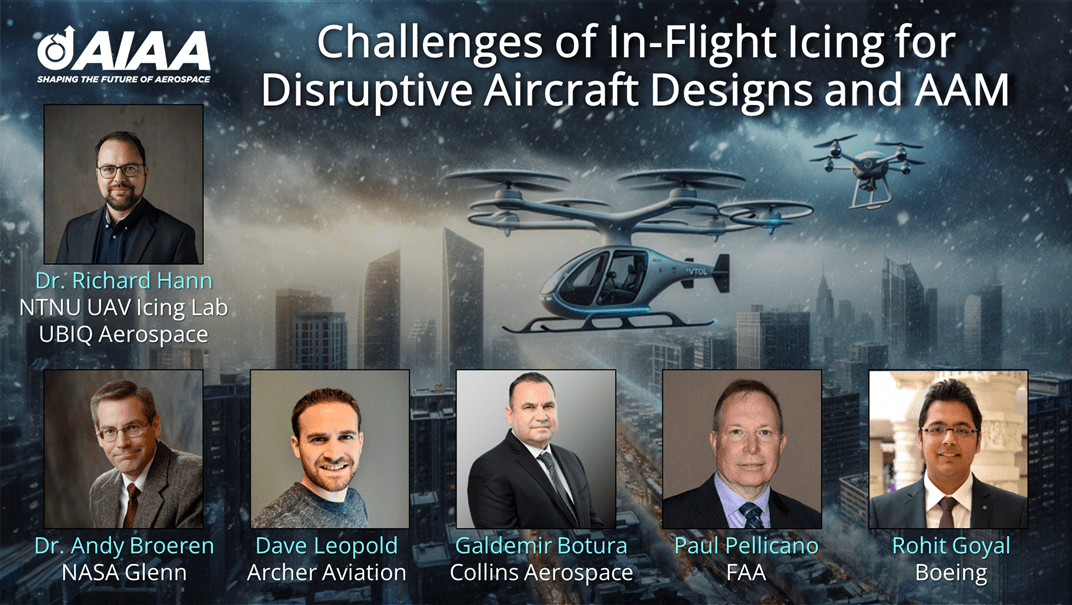

Reference: Lindner, M., Hann, R. (2025). UAV Icing: Icing Effects on Control Surfaces, AIAA AVIATION FORUM AND ASCEND 2025, doi.org/10.2514/6.2025-3388